I was born and bred in Nottingham, but my parents came here in 1962 from Ghana. We were the only Black people on the whole of the street where we lived. I went to a Catholic school, where me and my brother were the only Black people. There were a lot of kids running around the school, calling us the n-word, and ‘Blackistani’. We came from a generation where our parents were taught to do as they were told, so even if we felt that we were being hard done by the teachers and the children, we just ‘put up and shut up’ so to speak.

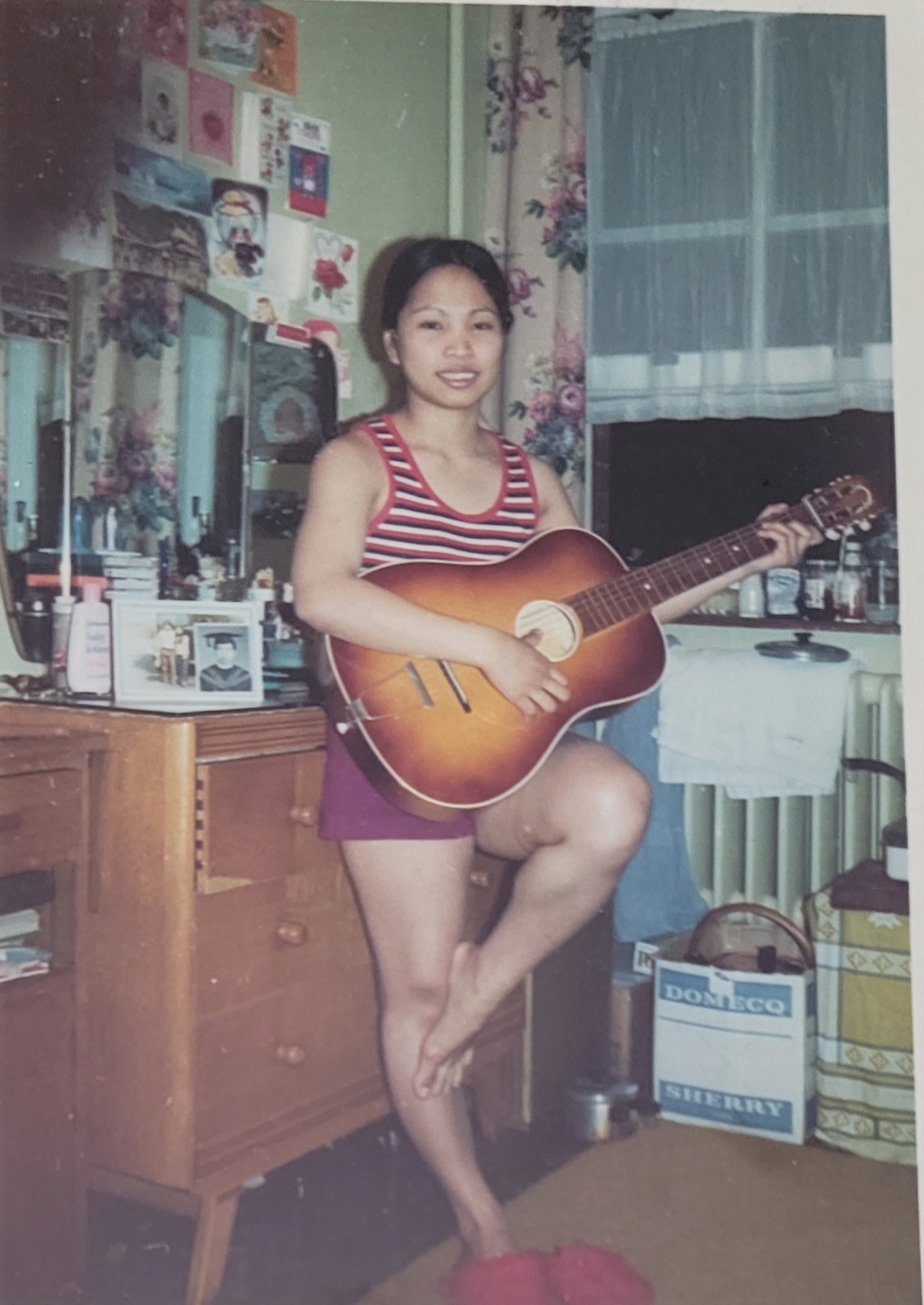

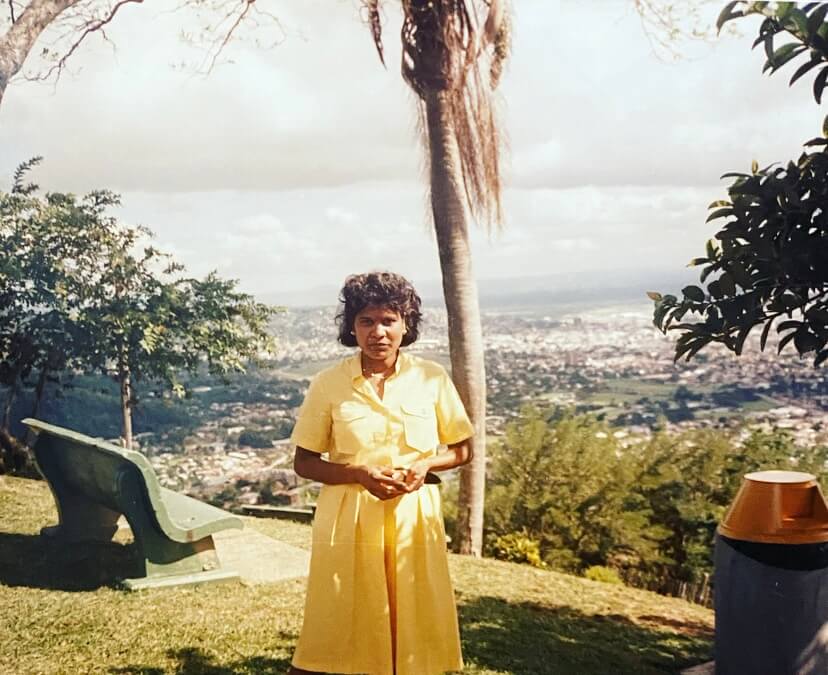

Sylvia Owusu-Nepaul

When I was a teenager, you would be walking through town and there’d be the National Front marching and you’d have the anti-fascists. It was the time of Margaret Thatcher and high unemployment and people were always looking for somebody to blame – pretty much like it is now. It could be very intimidating because you didn’t know who was who.

At home we spoke both English as well as Twi, which is one of the Ghanaian languages. My parents would always speak to us in English but would speak to one another in Twi. Because we were going to go to English schools, they made us assimilate to the English language. We had elocution lessons at home. My dad would say, “Right you must apply the dictionary”, so every one of us was absolutely brilliant at spelling because we were taught that way.

Originally, I wanted to be a musician. I had to assimilate into a society where you must make sure that you have got a good career before you do anything that you really want to do. I think that is a general consensus of African parents because they feel that education is hard to come by in other countries. My mother was a nurse and a midwife and she trained here in England and she encouraged me to go into the health field.

I’ve been in the NHS since 1988. The hardest part has been in my midwifery career which I started in 1991. When women are in pain or they are using Entonox (gas and air), they say things they wouldn’t normally say. I think sometimes their pain exacerbates how they really are in person.

I’ve had people say that they don’t want to be looked after by Black midwives and that they don’t like Black people. That’s hard. And to a degree, I will accept that because you are in pain. What I find really difficult is when you are working with colleagues that probably have the same attitudes as some of those people.

I find that Black patients get a raw deal. I’ve got many colleagues who can vouch for that. There are even papers that have been put out that show that as a Black and ethnic minority, and especially an African and Caribbean woman, you are more likely to die in childbirth than the average white counterpart. I always go the extra mile. And that’s not to say that I wouldn’t go the extra mile for a white person because I treat people as equally as I can across the board. Because I know that we are still suffering, we have been suffering for the longest time, so if I can make your experience of being in hospital a little bit better, I will.

Sylvia’s story was collected by the Young Historians Project as part of their project “A Hidden History: African Women and the British Health Service, 1930-2000”. Find out more at www.younghistoriansproject.org