I came over from Manila in the Philippines in 1970 to train at the Westminster School of Nursing in London. I’m from a large family and being the oldest girl of nine children, I knew that I had to make some decisions about my future and fast! I had a personal goal of becoming a nurse, but my dream seemed almost impossible, not just because of the financial burden on my family, but also further education for females was not encouraged. I had six brothers and it was believed that they should go to college instead. A woman’s place was in the home in those days, but I didn’t want to stay at home and cook!

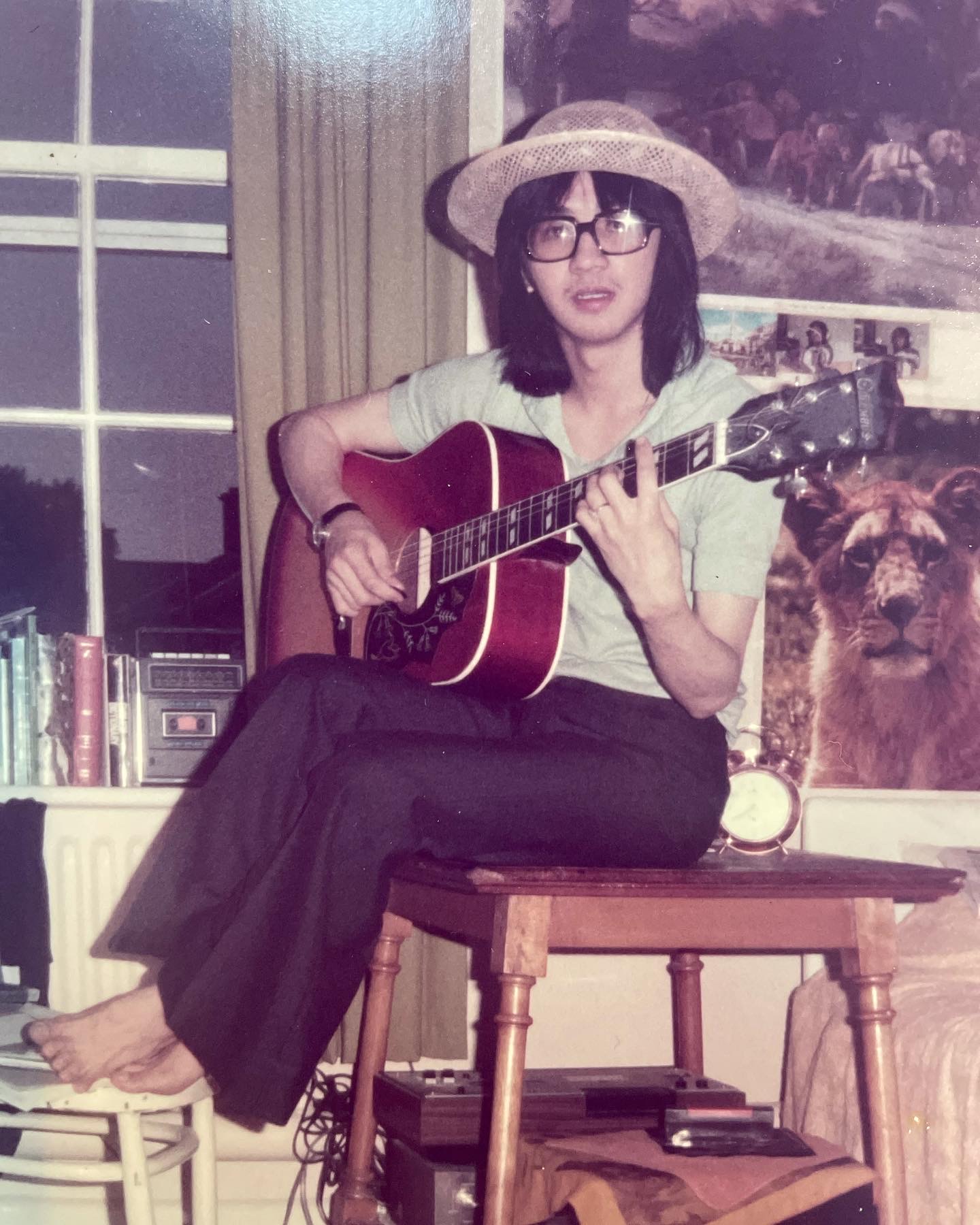

Connie Bennett

I was scared and excited at the thought of coming over. I hadn't even left Manila, let alone The Philippines. Leaving my family behind was a big deal. I was 20 and this was a one way ticket to a destination that I had only heard about on the radio or in black and white on TV. I remember crying at the airport. I hugged my father and told him that I would be back in two years when training finished. That was the last time I saw him alive.

My parents were so proud of me. Without this opportunity, they would have never been able to finance such training and education by themselves. My father, in the little English he knew, would show his employers the photo of me in his wallet and would proudly announce that his daughter was in London, studying to become a nurse! They were of course scared for my safety too. I later learned that my father didn’t sleep properly for weeks after I’d left.

It was not too hard to adapt to life in the UK. There was a group of us at the hospital Filipinos, English, Irish and Spanish nurses, but we all spoke English. We only spoke Tagalog with other Filipinos. Of course it wasn’t always like this. 1970s Britain wasn’t ready for an influx of immigrants. I remember once us Filipino nurses were on the bus. We were chatting in Tagalog, perhaps a little too loudly, when an English lady boarded the bus and told us to shut up and go back to our own country. Instances like this were common and in general, the British public weren’t that warm and friendly towards immigrants, so I would often feel isolated. However I must say that there was a lot of unity at the hospital itself.

But even though I had my ‘hospital family’, they couldn’t replace my actual family. It’s easy to forget that back in those days communication was mainly through written letters, so correspondence would take months and a phone call using the pay phone would cost you your month’s wages. When my father passed away, I found out the news through a telegram with the briefest of words (they would charge you per word) and going home for the funeral simply wasn’t an option. The British weather and bland food also compounded my homesickness.

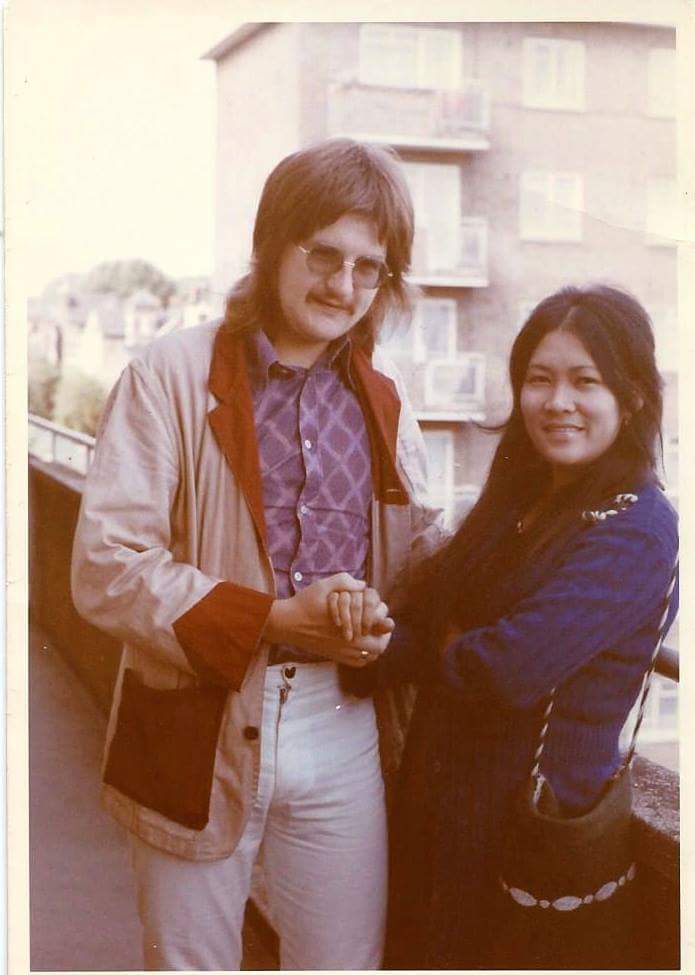

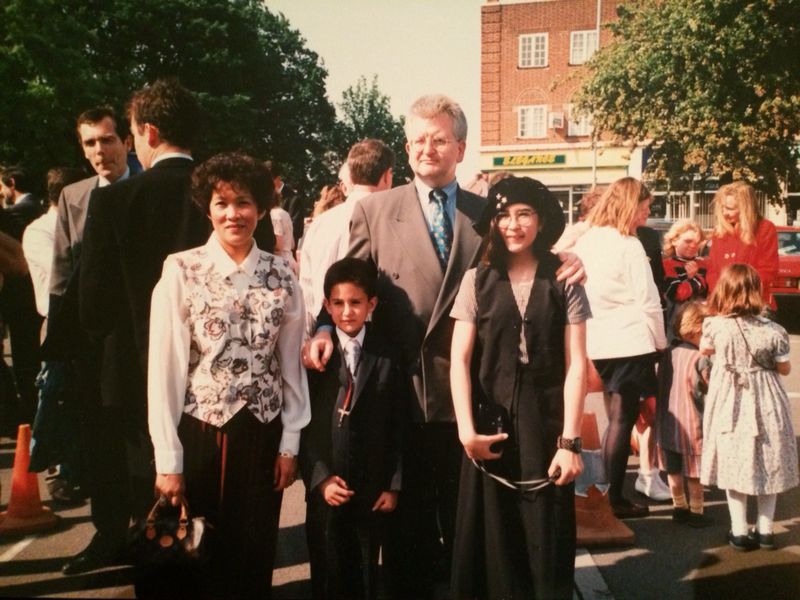

I met and married my husband within the first few years of being in London. I never planned for that to happen, but that's life! We went on to have two children, a girl and a boy, so my roots were laid in this country. My husband and I have just celebrated our 45th wedding anniversary!

The UK became my home relatively quickly because of my husband and children. I still miss The Philippines for the weather and the food, but I would never consider going back there to live. Like any country you move away from, it changes, it’s not the same place that you left all those years ago. Myself and many others like me left our birth countries for socio-economic reasons and unfortunately those conditions have not improved. I have fond memories and sometimes get nostalgic about The Philippines, but I’ll only go back for holidays.

Overall, I am very proud of my journey. Looking back, I don’t know how I managed to stand on my own two feet and I’m surprised at how strong I became. Yes, there were bumps in the road, but that’s life. Allow me to speak on behalf of my fellow Filipino friends and colleagues who are no longer with us: we are content knowing that we managed to support the NHS and to contribute to the country that adopted us. During our time on the wards we were also able to change the minds of British people that didn’t want us here initially, to show them that we weren’t here to take advantage of the UK. We demonstrated to the British public that we are loyal, hard working and dedicated to our jobs and in turn changed the negative mindset of immigrants being in the UK workplace.

After 46 years of working as a Practice Nurse for the NHS at Chase Farm Hospital, Enfield and Haringey Health Authority, I am enjoying my retirement! My husband and I have a passion for travel, but that has been on hold since the start of the pandemic. My two children have immigrated to other countries (I suppose I started a trend) and we always look forward to getting together as a family. My son and his partner had a beautiful baby during the pandemic, so I'm excited to meet my grandchild for the very first time!

I love that we created a community of Asian and SE Asian nurses while working for the NHS, and we became this network of extended family. Throughout the 1980s some got married and had children and those children would become friends. It was a happy time where everyone was invited to celebrations filled with food and laughter. We supported each other and made this our home away from home.

Nevertheless, being so far away from my family was the hardest. I couldn’t go home immediately after my father died and when my mother was diagnosed with terminal breast cancer in the 1990s, I couldn’t be there to look after her. That was a very difficult time. In terms of work, having to inform a family that a family member had just passed and console them, that was really difficult. It never gets easier, but doing it for the first time, in my early twenties, that was tough.

The journey was long, but I have no regrets. I am happy in the knowledge that I have served the country that I call home.

This story is part of Ingat-Ingat (http://www.ingat-ingat.com/), an exhibition curated by Becky Hoh-Hale about Southeast Asians who came to work for the NHS between 1959-1979.