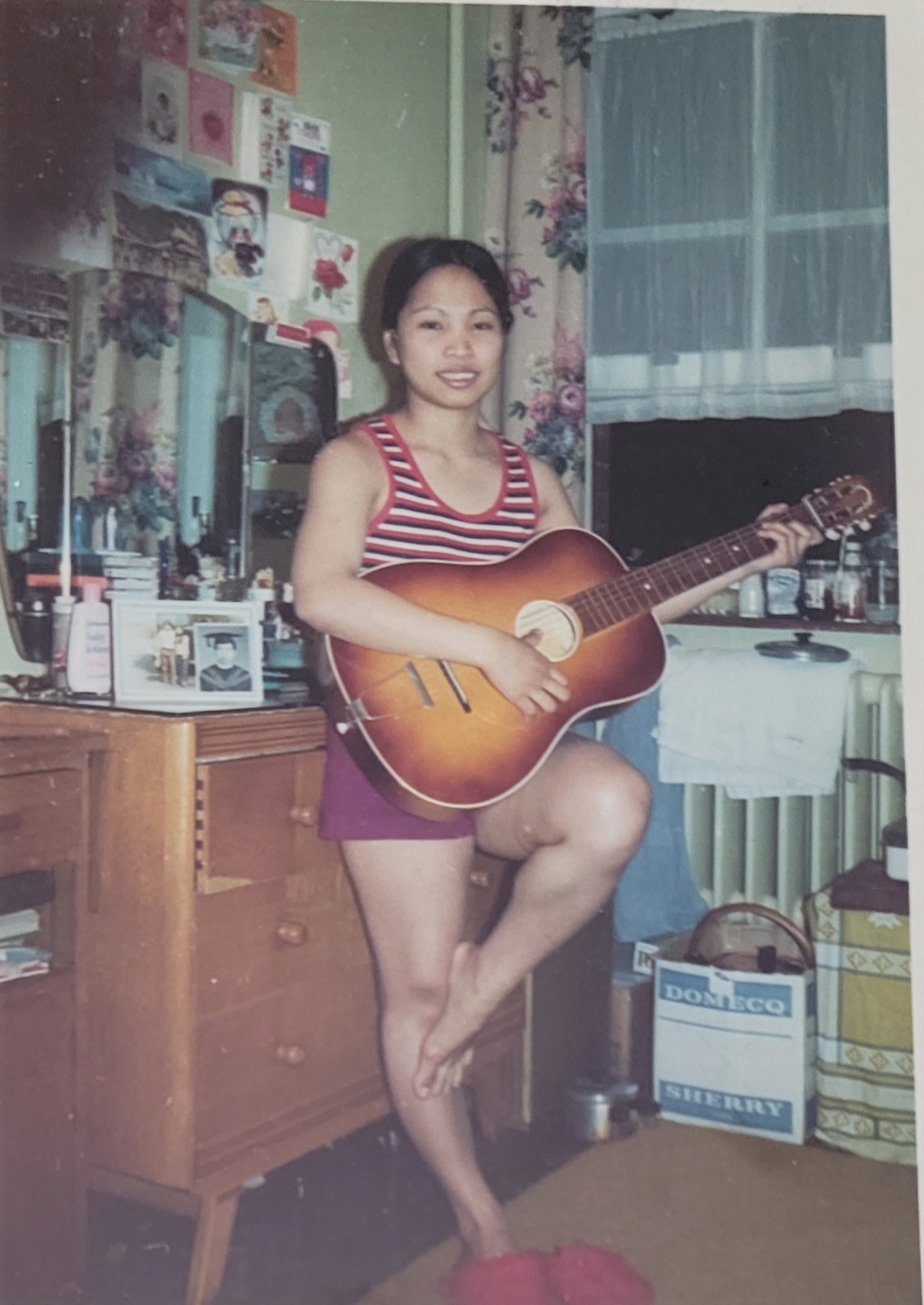

I travelled from Malaysia in 1959 to train to be a nurse at Edgware General in London. I wanted to be independent. My cousin had already came over, and suggested it. I didn’t realise it would be such hard work! My eldest brother managed to get me onto HMS Corfu. He booked first class for me from Singapore, then Penang, then Port Klang, 28 days! I was just 19. My purpose was to finish all the training, and then go home. Then I met my husband and that was it! That was the end of going home!