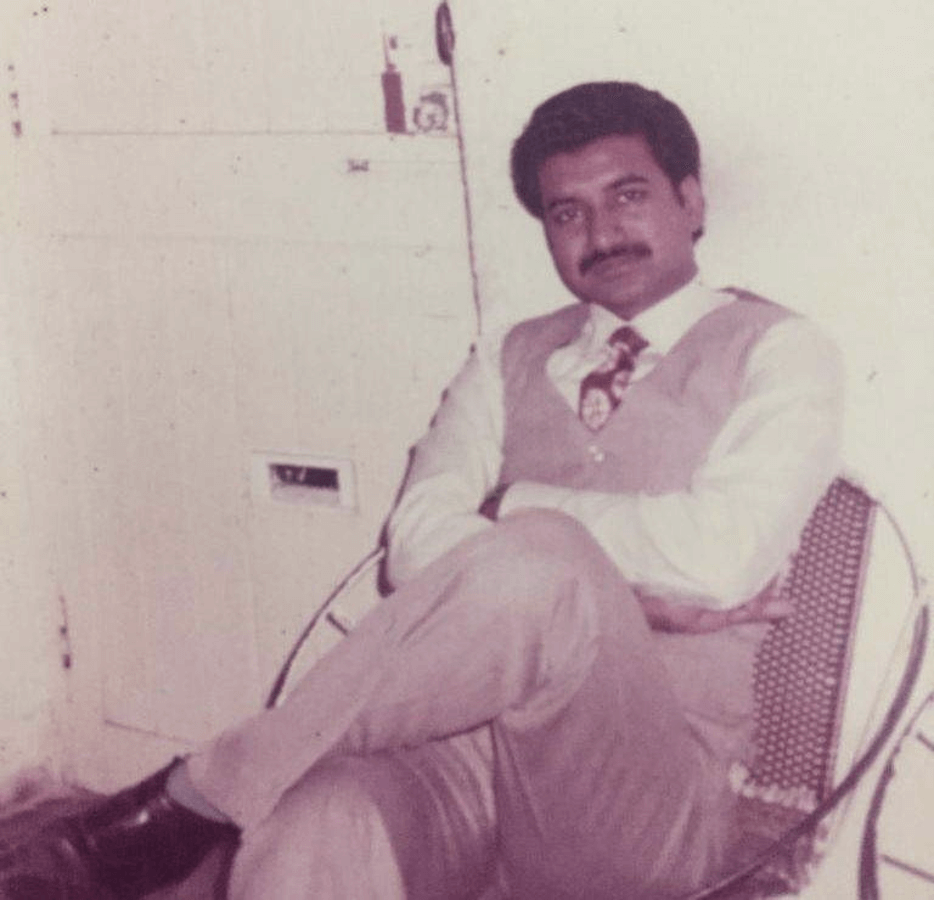

Before the independence of India from the British Empire, Britain brought workers from India to East Africa to build the railways. That’s how my family came to be in Kenya. Political upheaval began in the late 1960s and my dad got concerned. He thought we needed to move out before there were any major issues. Because we had British passports as a result of Kenya being a former British colony, we were advised to come here. My dad came first and the rest of the family came about a year later.

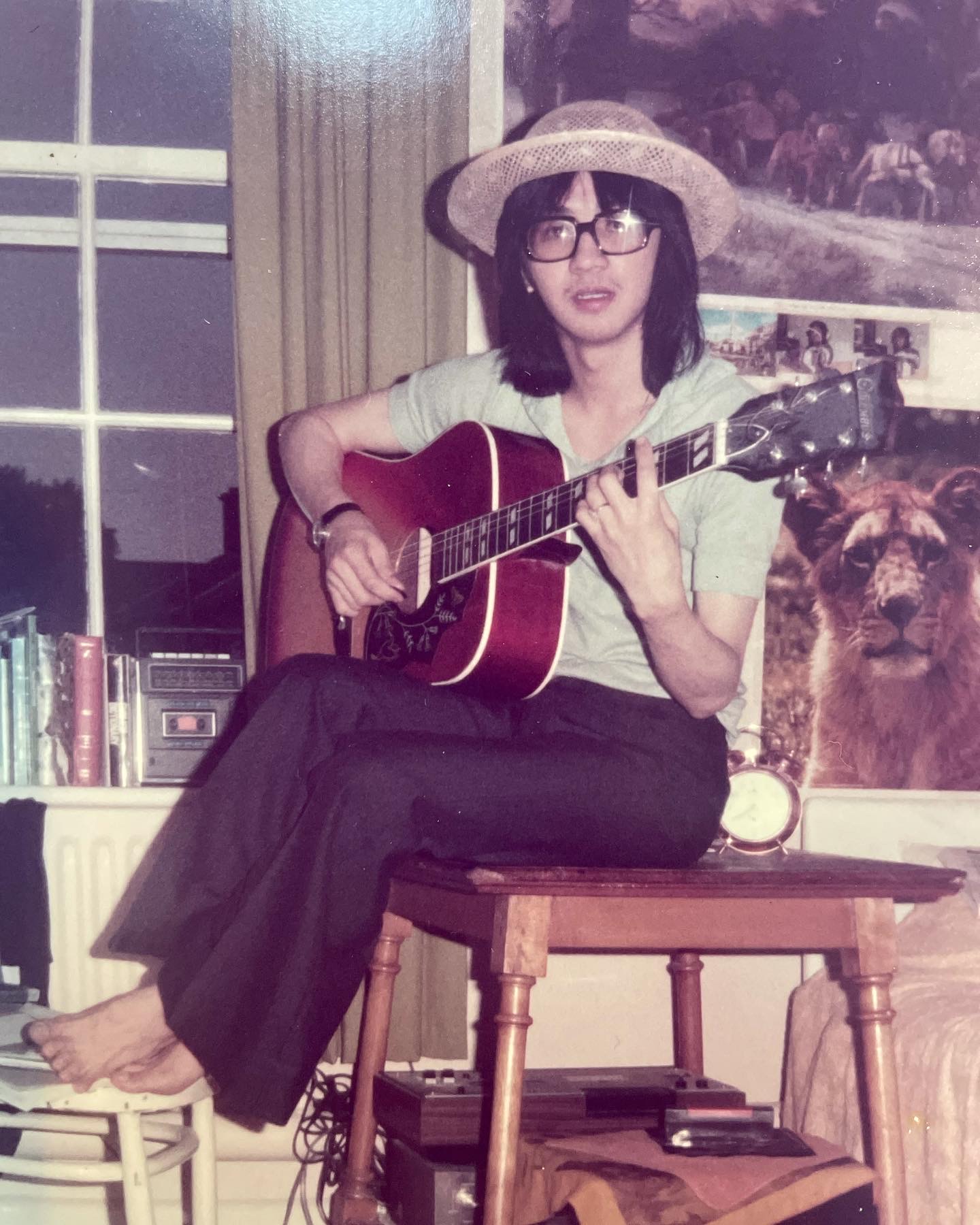

Jyotsana (Josh) Raval

Our education in Kenya was quite good and all in English. All the exam papers used to come from Oxford. Although there were lots of little differences in Britain – a sense of humour, the accent – we settled in quite quickly.

Once I did my GCSEs, I didn’t know what to study. I wanted to do something with people, rather than an office job. Nursing was the job I took because, as a student, we got paid a little bit and that made a difference. Although I was 18 at the time, I was quite naive because we came from a smaller town and I wasn’t really streetwise. I was shy and I was always frightened to say things to patients because I didn’t want to get anything wrong or upset somebody.

When I started, there weren’t many Indian or any other ethnicities in nursing at the time. I ended up interpreting for a lot of Indian patients in Gujarati. Some had their own ways of doing things that were strange to some of the doctors, like taking herbal medication. Once when I was working in A&E, an Indian lady got her hand burnt, and she put turmeric on it. The hospital staff thought that was very strange. Of course now people know that turmeric is a power food.

There were lots of little things, although it didn't upset me. I just thought, ‘These people don’t understand. Why do I have to explain it? This is how we do things’.

There were the odd patients that didn’t like being looked after by an Indian, but then they got used to me. When I think back now, some of the comments were racist, but I didn’t realise at the time because we were brought up to expect racism, which was happening in my dad’s life and everybody’s life. My dad told us, “Don’t take it to heart, just get on with it. For every one person that’s racist, there’s hundreds that aren’t.” So that’s how I dealt with it.

After having worked as a staff nurse on a ward, I went to do my midwifery training, and then started my job as a midwife. And I’ve just retired from Leicester Royal Infirmary as a labour ward coordinator.

From when I started and to what I was doing at the end, I wasn’t the same person! I was communicating with different professionals in different ways: obstetricians, anaesthetists and midwives — continuously, all day all the time. They’ve got their own views and sometimes they don’t agree with each other about how we were doing things and then trying to keep everybody happy when you’re in charge, or continue and resolve things so you don’t take it home with you. Working with severely ill women and severely premature babies made the work very intense all the time. It was quite challenging, but I really enjoyed it and meeting different people.

When I started, people could not pronounce my name. I tried to tell people how to say it for three months and in the end I just said, ‘Call me what you like!’ I was called Josh. I’ve stayed Josh and it’s grown on me.