My father was a senior physician in Poland when the Second World War began. He spent the war fighting the Russians on the Eastern Front where he was arrested and sent to one of Stalin’s labour camps. Although he was a prisoner, the Russians kept him alive because he was a doctor and he could help them. His first wife and child were shot by the Gestapo, and virtually his entire family were killed by the Nazis. So when he came to Britain in 1946, he was in despair. And then he had to start his career all over again at the age of 50.

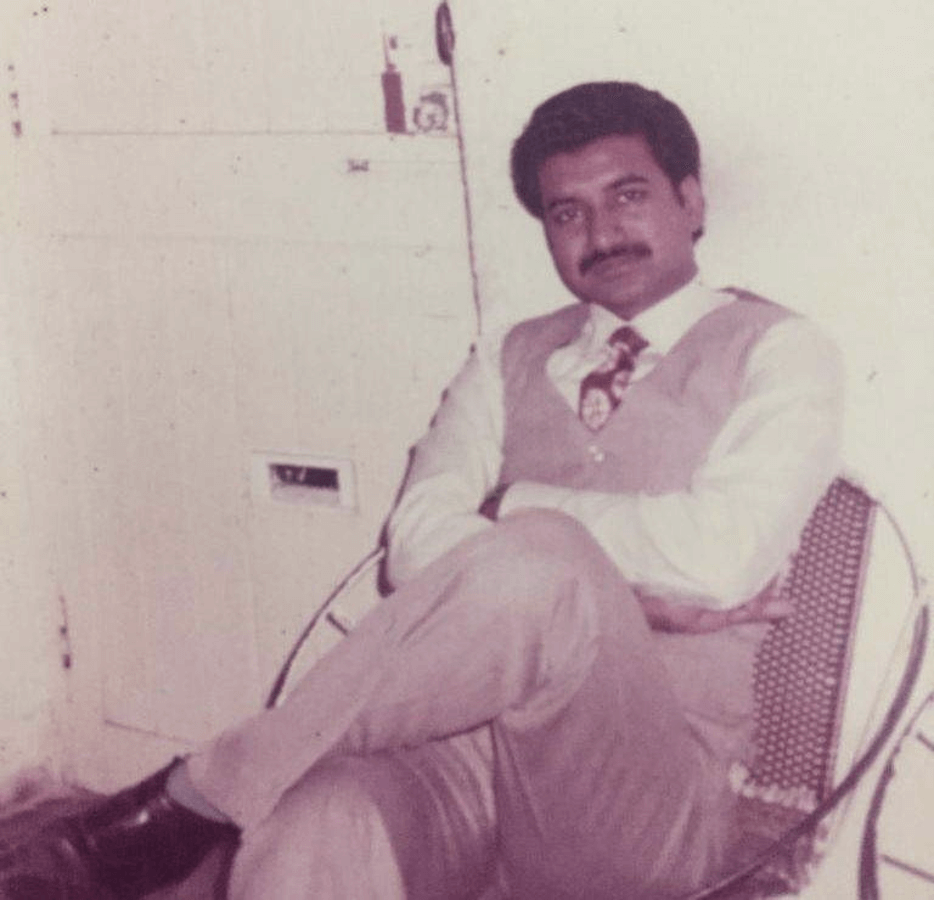

Joachim Weinreb

People sometimes told him to go back to Poland, but he wrote, 'I can’t go back and live at a cemetery where eleven members of my family are buried, grown ups and children murdered by Nazis – go back to the place full of reminiscences of a happy past life and in addition can I go back now to the conditions of slavery which I only too well know'.

When my parents first arrived, they went to Sheffield, where my father had a series of short term jobs. He was praised for his work but was told that he would have to wait about two years until all available British doctors were employed. Immigrants or refugees, like my father, were at the bottom of the hierarchy. He felt he was discriminated against not only because he was a foreigner, but also because he was old.

He said, “I collected testimonials and left Sheffield unwillingly and despondent that after 14 months of attendance at the Hospitals and friendly relationships with all I was not given the slightest hope to obtain a job even in the future. In London I called the agencies but they didn’t give much hope either because of age.”

My parents thought that because they fought in the war alongside the British, that they would be looked after better when they came here. Of course they were allowed to get residency and my father was allowed to register as a doctor. But he didn’t think it would be such an uphill struggle.

Eventually he decided to go into general practice and opened his practice in 1951. He worked in Kilburn in North London, partly because that was the only practice he could get. My mom cleaned the surgery and helped out with paperwork and kept the surgery going. There was no other person working there – no nurses or anything like that. They did everything themselves.

At the time, Kilburn was a pretty poor place. It was where immigrants lived, particularly the Irish and subsequently the West Indian population. In the NHS in those days, you paid for some services, like certain vaccinations. A lot of the patients couldn't afford them and they would pay in other ways, like fixing the guttering or a bottle of whiskey or something like that.

My father wasn’t a particularly touchy feely person; after his experiences, you can imagine that. He was very blunt with his patients but he gave them good advice, and I think his patients appreciated that.

Growing up, my parents house was always filled with Poles and Polish was spoken. Although my mother was Catholic, we kept some Jewish customs alive as well. But at the same time, I had this double life because I went to English schools. My father died when I was 30 but my mother was very present in my life. I grew up most of my life not knowing anything about my mother’s past, I will never know anything about my father’s past now that he is gone.

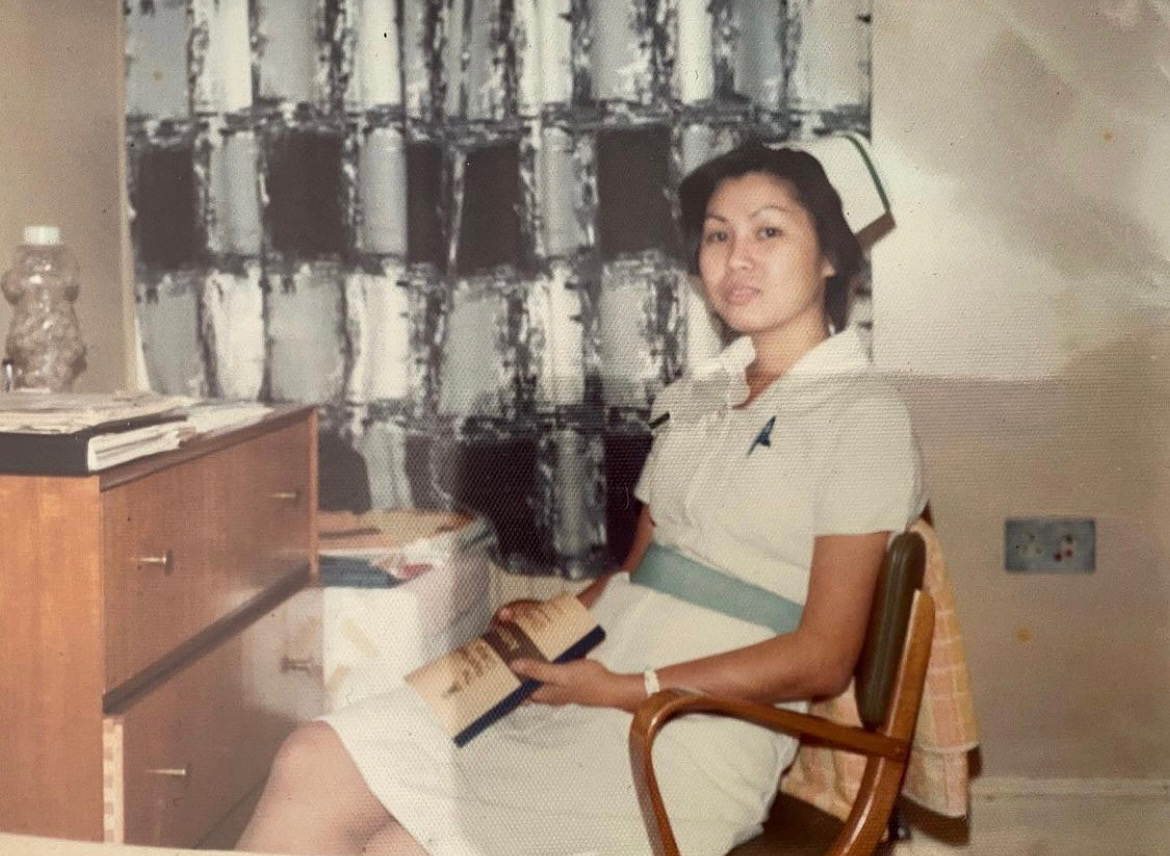

I also worked in the NHS for 40 years, but in a very different place than my father. My mother was absolutely determined that I would be a doctor. Having come from a poor immigrant background, she wanted me to do better. She didn’t want me to struggle like she did.

Told by Irene Weinreb