For many migrant healthcare workers, the difficulties were by no means confined to work. Some faced discrimination or hostility when finding a place to live. Others struggled to balance their families’ needs with the demands of their jobs. But in spite of these challenges, people created homes, forged friendships, started families and contributed to the communities in which they lived.

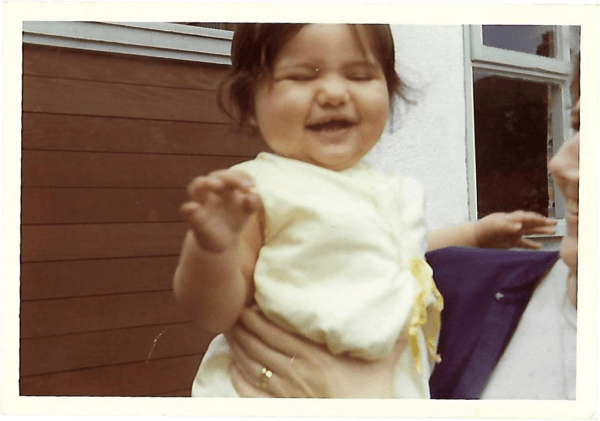

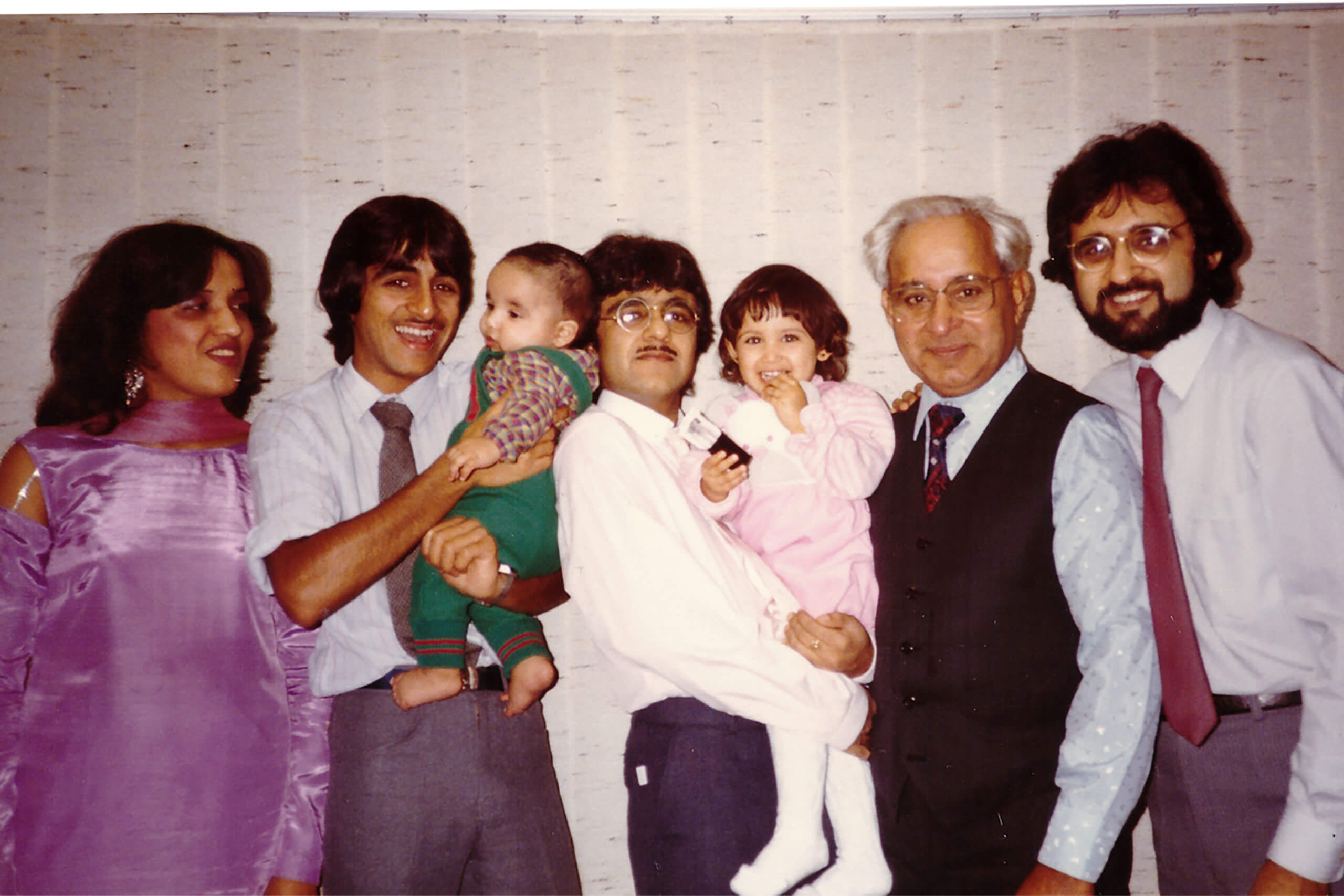

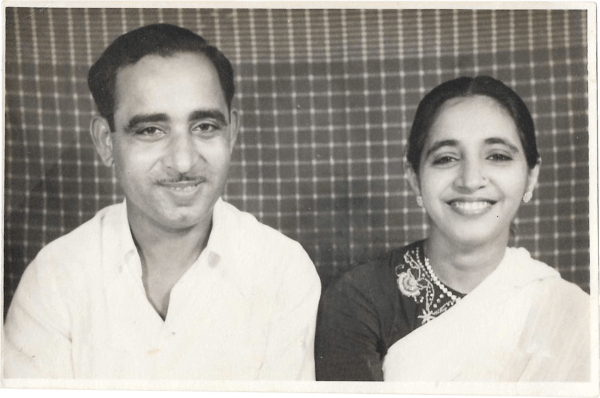

Dr Hargundas Khanchandani with his children and grandchildren. Image courtesy Raj Khanchandani

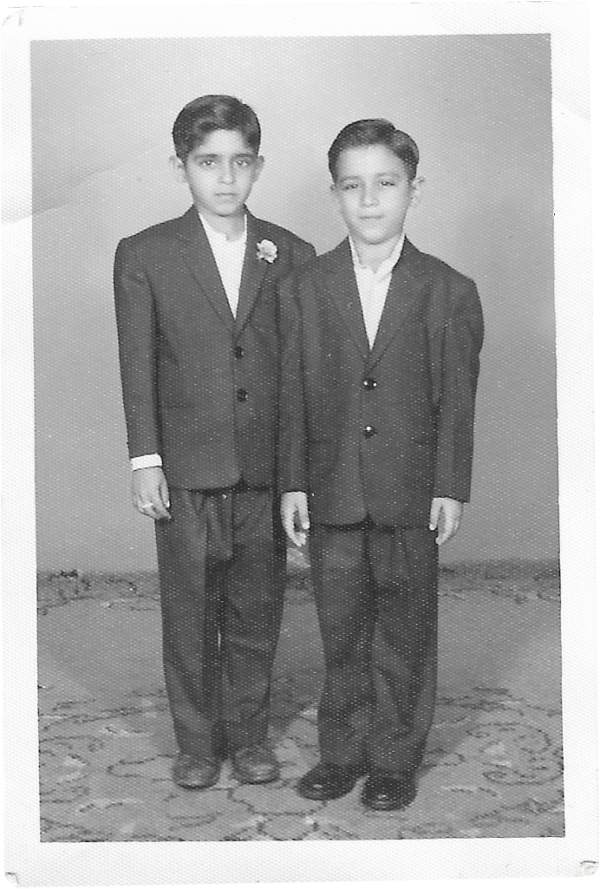

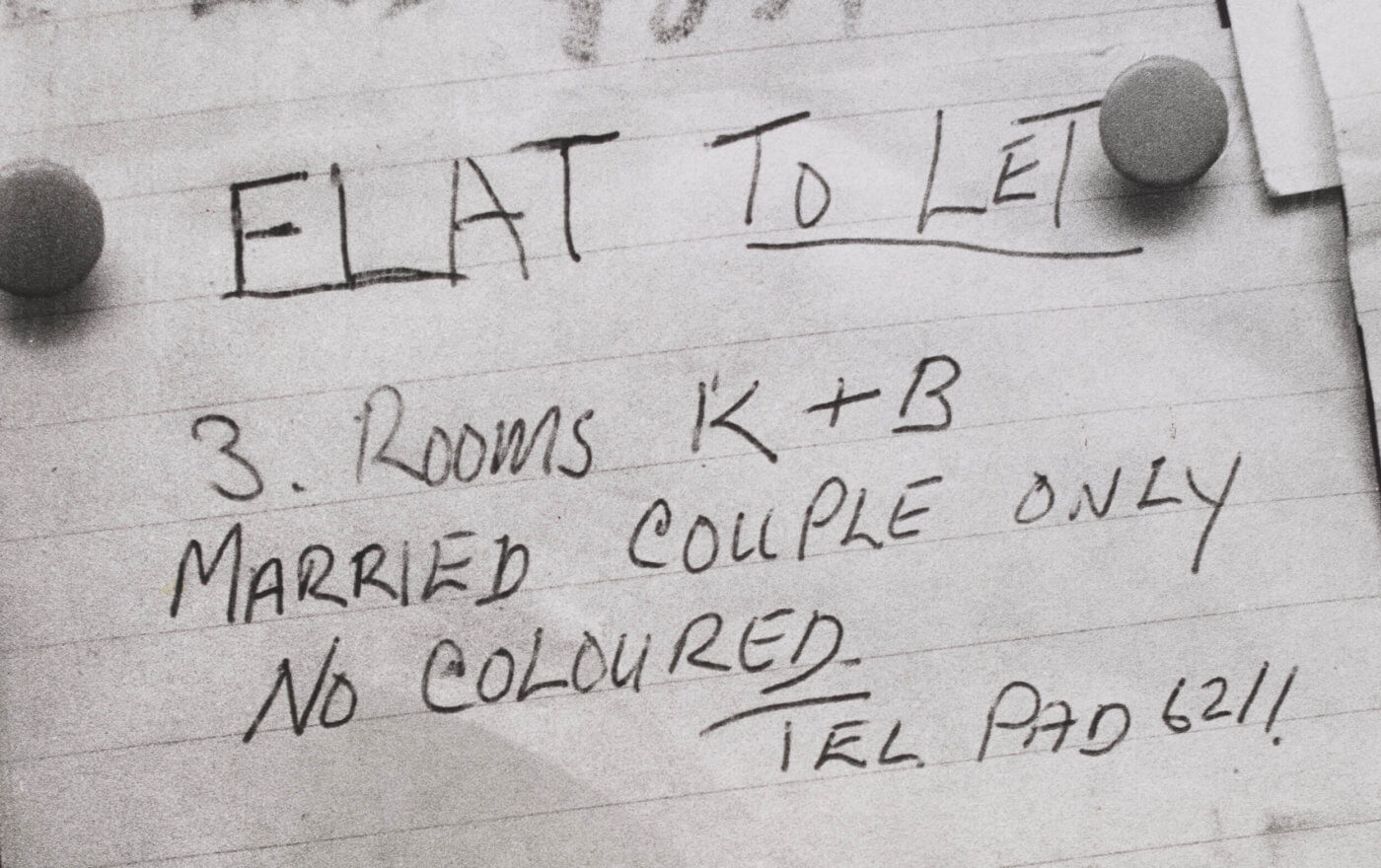

© Charlie Phillips / www.nickyakehurst.com

We kept looking for a flat but there was a lot of colour prejudice in Cambridge in 1967 – there were signs saying NO ASIAN. We would turn up and the landlords would tell us the flat was gone. Eventually I begged Mr and Mrs Lee who had a flat to offer if we could stay. He liked the look of us and after that they became our foster parents or, say, guardians. We shall be grateful to them for the rest of our life.

You spoke to people and they never spoke, you would walk down the road and they would cross on the other side. The British Council had taken us through what to expect. What they didn’t tell you to expect was the amount of prejudices and discrimination that you encountered.

Having said that, at the time that I came there was a group of people that went into nursing from Barbados, so you had company. You had people who you could share all sorts of things with: disappointments or abuse.

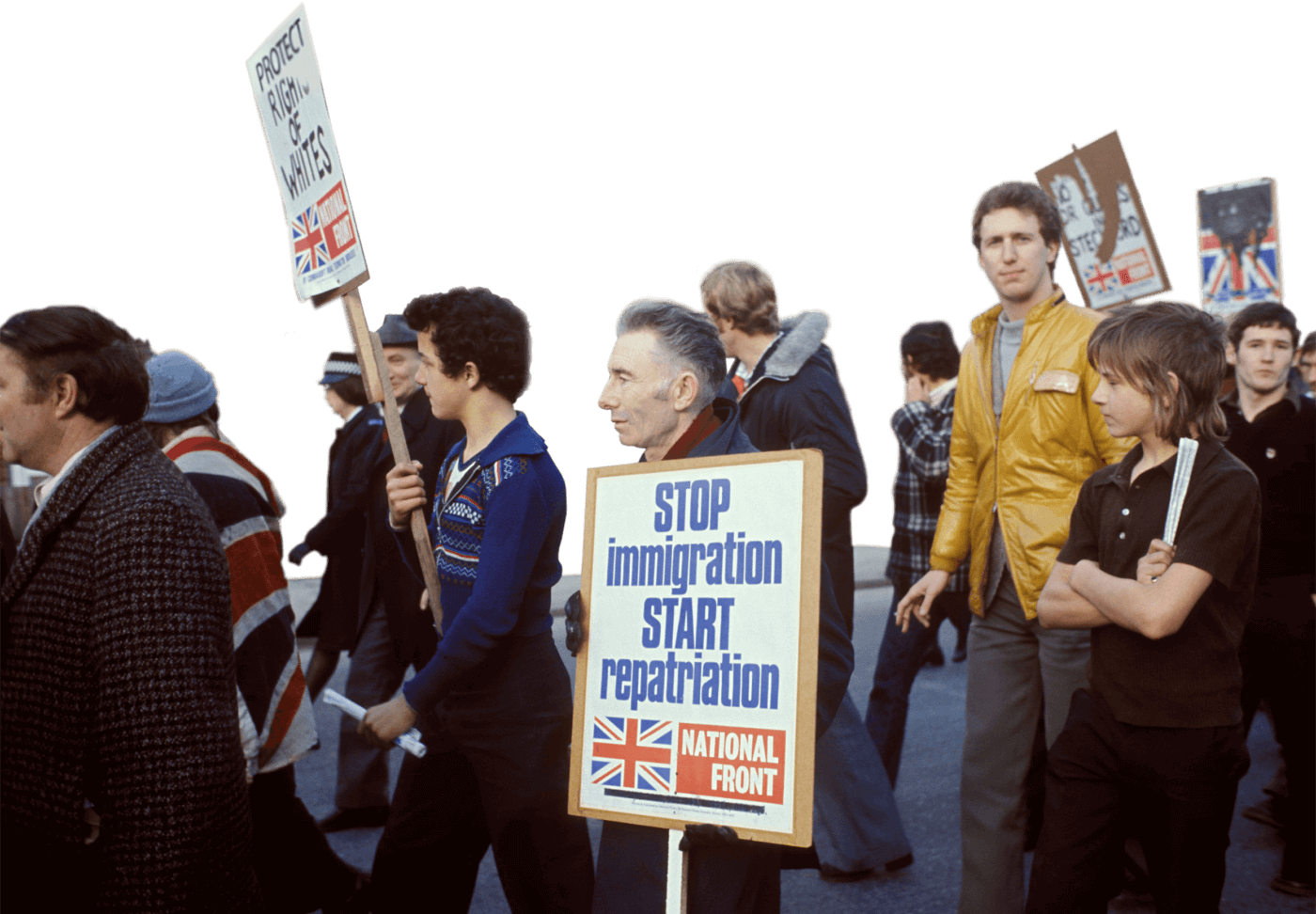

In the late 1960s, the National Front used anti-immigration rhetoric to gain support across the political spectrum. Soon, NF members were holding street marches and sometimes violently attacking people in Black and Asian communities. In response, young activists, many from minority ethnic backgrounds, organised antifascist and antiracist campaigns.

This was the difficult environment outside of work that many people encountered.

National Front March and Rally Walsall, Birmingham, 1970s Credit: Homer Sykes / Alamy Stock Photo

Life journeys

Sometimes you go into a patient’s room and then you think, ‘My daughter has a music lesson. I can’t be late.’ So how do you do that when you're talking to parents about a life or death situation? You truly have empathy with your patient but you’ve got other competing interests.

You're also a mum and a wife.

Building a community

Outside of the workplace, people followed their passions.

From getting involved in their local schools to mentoring disadvantaged young people to starting international charities, this work left a lasting impact on communities.

Allyson Williams MBE

"My husband Vernon was one of the founding members of the Notting Hill Carnival and he took me to a workshop where fellow Trinidadians were making costumes. It felt like home. We formed our own Mas band called Genesis. That first year we made more than 400 costumes. It was completely overwhelming!"

Dr Muhayman Jamil

"In 2012, when the Paralympics were being held in London, a French group of skaters and wheelchair users called Mobile en Ville approached us to help plan a route. I joined them in Paris and we brought six people in wheelchairs, pushed them all the way to London".

The Windrush

Generation

These photo etchings by artist EVEWRIGHT are a testament to the resilience and contribution of the Windrush generation to the NHS and wider society. For more information, visit www.evewright.com

Growing up in the NHS

The NHS is often referred to as a family – in some cases, literally. Many children of migrant NHS workers are following in their parents’ footsteps, carving out medical careers for themselves and furthering their parents’ legacy.

My mother worked as an auxiliary nurse and she used to take me with her occasionally when she was on duty. It was fascinating seeing how they were with patients and how they looked after people. I loved their uniforms. And from a very early age I wanted to be a nurse.

Nurse badges. Courtesy Margaret Elizabeth Jaikissoon