My father was born in 1899 in Tost, a small village in Upper Silesia, Germany. The family was Jewish but considered themselves very German. My father had a brilliant career in his field of neurology and neurosurgery, and was expected to become the top neurosurgeon in Germany.

Sir Ludwig Guttmann

When Adolf Hitler came to power, most Jews and intellectuals thought he would not last, but sadly they were wrong. A law was passed forbidding Jewish doctors, teachers and academics and scientists from working in non-Jewish establishments. My father was dismissed from his post immediately and became the director of the Jewish hospital in Breslau (now Wrocław in Poland).

As the situation deteriorated for Jews in Germany, he secretly made contact with the British Society for the Protection of Science and was given a research position at the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford.

We left Germany in March 1939 leaving behind several members of our close family who we never saw again. In Oxford, where we arrived penniless, we stayed in the Masters lodging in Balliol College. My father did research work on peripheral nerve injuries and my brother and I started school.

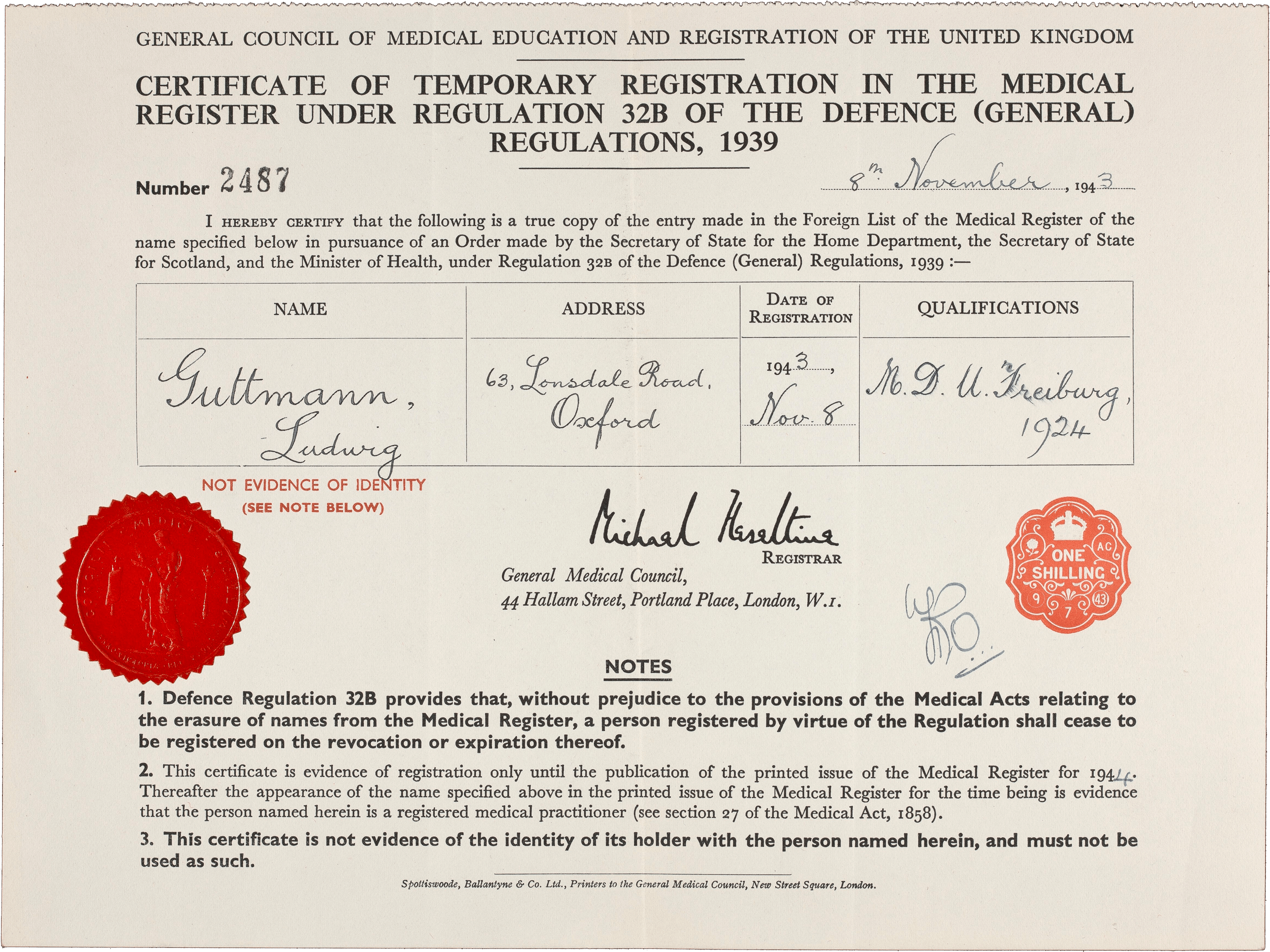

Dr Guttmann's Certificate of Temporary Registration in the Medical Register. Credit: Wellcome Collection

From the day we arrived in England, my parents said we will only speak English and I remember finding it very difficult at first. I cried a lot.

In 1943, my father was asked to open a spinal injuries unit in preparation for anticipated casualties from D-Day and the Normandy landings. At the time patients with injury to the spinal cord and the resulting paralysis below the level of injury were not expected to survive very long and many died of severe pressure sores and urinary infections. It certainly was not a task which appealed to anyone in the medical profession but my father was excited at the thought of having his own department again and treating patients. He already had very definite ideas on the treatment of spinal cord injuries.

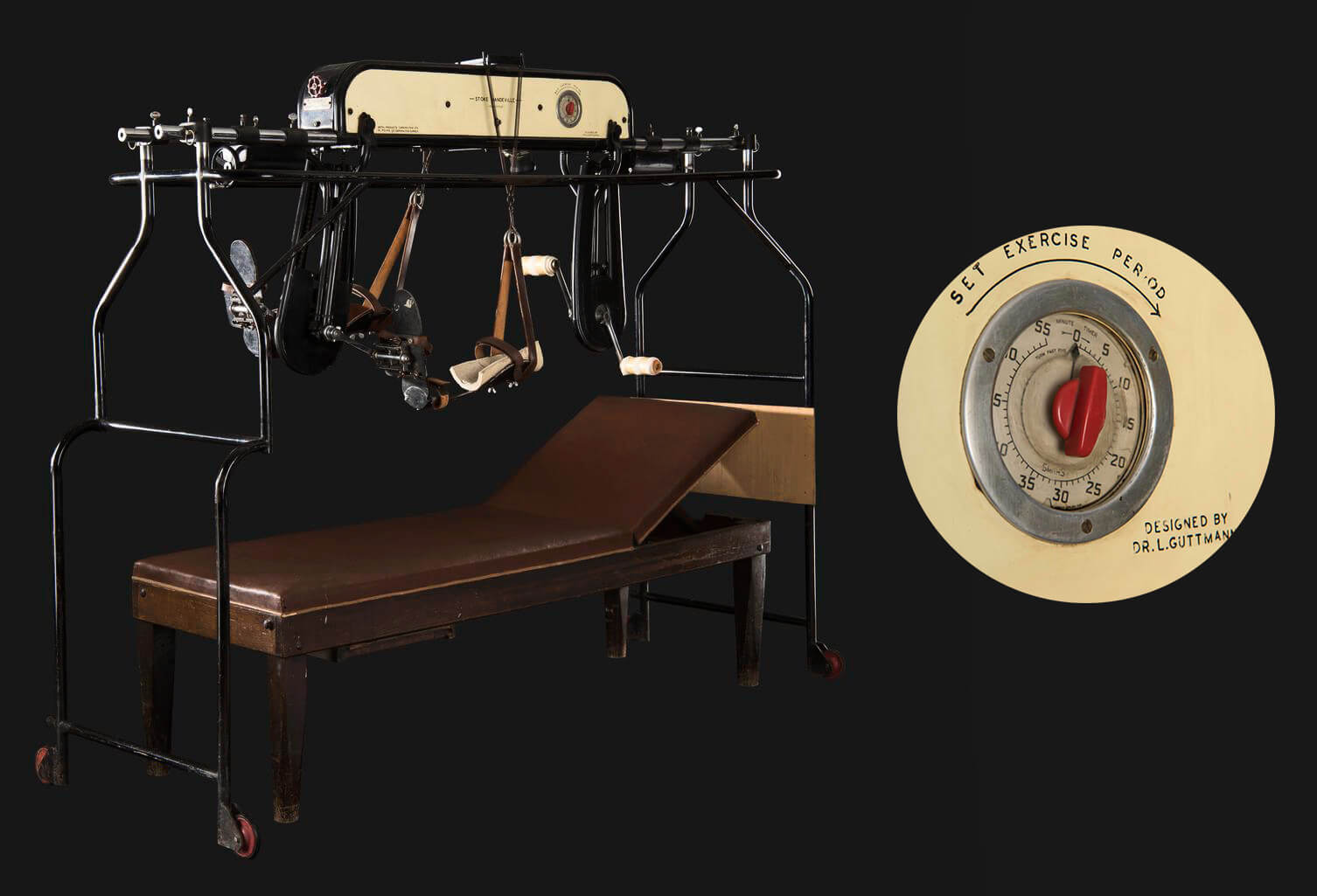

Designed in 1949 by Dr. Ludwig Guttmann, the bed cycle was used as an exercise bike for both paraplegics and tetraplegics. The metal bar would be placed over your bed and you’d push the pedals with your hands, building muscle in your arms and upper body. Credit: The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Step-by-step under his leadership the scheme of physical restoration was developed. Because of the success of the treatment at Stoke Mandeville all patients with spinal cord injuries were eventually sent there and the unit ended up with 190 beds.

In those early days virtually all the patients were servicemen who accepted discipline. And in spite of his very authoritarian manner, my father was generally known as ‘Poppa’. Patients had to do some regular work even when laid up in bed for many weeks. Gradually they started doing some sports because my father realised that this would be a very good way of integrating these young men into society. First of all they started doing archery and gradually more sports became popular, especially wheelchair basketball.

In 1948, on the day his majesty King George opened the Olympic Games in London, two teams of 14 paraplegics competed at Stoke Mandeville. These were the forerunner of the Paralympic Games.

My father died in 1980 and I feel his life was one of adversity turned into triumph, not only for himself but for the very many disabled people who now take part in sport at all levels.

Told by Eva Loeffler OBE

Credit: Wellcome Collection

Credit: Wellcome Collection

David Weir crosses the line first to win the 1500 Metre T54 Final at the London 2012 Paralympic Games. Credit: Clive Chilvers / Alamy Stock Photo

If I ever did one good thing in my medical career, it was to introduce sport into the rehabilitation of disabled people.

A patient's story

My father was shot through the lower back and left for dead near Anzio Beach in 1944, rescued by his sergeant who picked him up as he looked light enough to carry over his shoulder. He was taken to a US military hospital in Naples and told that he would never walk again or have children. He was transported back to Britain on a US hospital ship – from which he heard Vesuvius’ last eruption of 1944 – and spent several months immobile in Frenchay Hospital.

This is an extraordinary picture of my father lying in a hospital bed as he is inspected by the then Queen Mother, Queen Mary, during a Royal visit.

Later, at Stoke Mandeville Hospital, my father was treated by Ludwig Guttmann who made a deep impression on him as someone who both cajoled and inspired his patients in equal measure. Guttmann’s revolutionary approach transformed outcomes for spinal injury patients like my father who, though profoundly disabled throughout his life, did indeed walk again and went on to have four children and a successful career.