I left school at fifteen after passing the Intermediate Certificate. After a few years of working at low wages in Dublin and Killarney, I felt there was no future for me in Ireland at that time. Most of my friends had gone nursing to England. My mind was made up practically overnight that I would go to England.

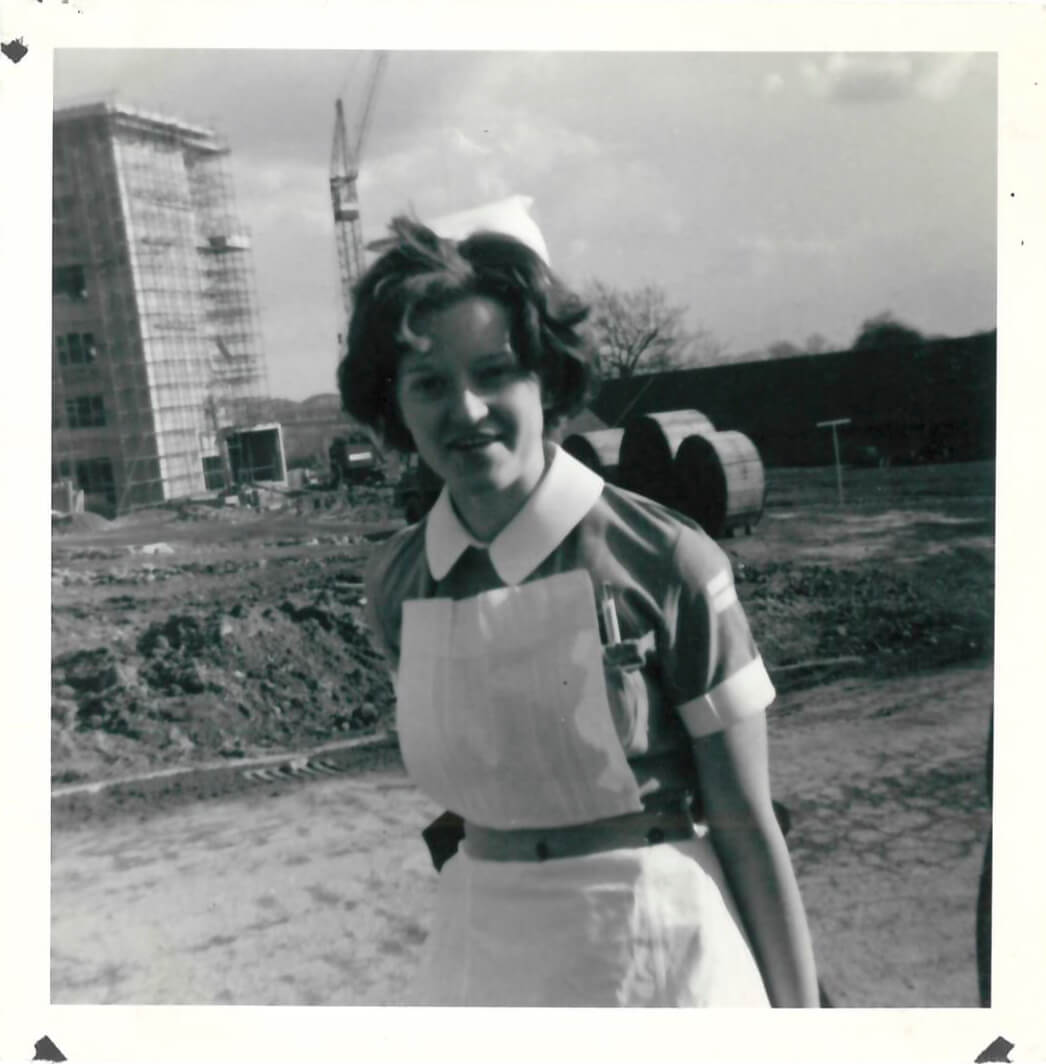

I answered two advertisements for student nurses in The Universe, a Catholic publication which I thought would only have reputable hospital advertisements. The City General Hospital, Stoke on Trent was the first to reply. Within a few weeks I received a letter of acceptance with an invitation to start as soon as possible, as a pre-nursing student before the next preliminary training began in two months.